Old wine in new bottles...

If it looks like the Front National and sounds like the Front National…

I know it’s been a while, but I’ll plead the headaches. Events at Lille over the weekend of 10-11 March have, however, given me both a theme and a flow.

So, the weekend marked the Front National’s congrès de refondation, the culmination of (it says here) a period of reflection on the 2017 presidential and legislative campaigns, a broad and deep consultation of the membership on a range of issues the leadership deem central to the party and, as the principal tease, the promise of a change of name for the party.

To recap briefly: Marine Le Pen expected to go through to the 2017 presidential election run-off in first place. She finished second, behind Emmanuel macron and not very far ahead of François Fillon. Then, she expected to get 40% of the vote in the second round, but after a poor inter-round campaign and a disastrous head-to-head debate with Macron, she took just 34%. In the general election that followed, the party took just eight seats, and even one of them has defected since. In any other party, Le Pen would be toast, but populist far-right parties don’t behave like mainstream parties and this one is built around a dynasty. Instead, Le Pen jettisoned her main strategist, Florian Philippot, éminence not all that grise of the process of dédiabolisation (detoxification of the party image) last autumn and embarked on a process of ‘consultation’ of the grass roots, or whatever is left of them.

According to Le Canard enchaîné (24 January 2018), membership, and more specifically party subs, have taken a nosedive, which makes the recent ruling that banks should not refuse loans to the FN even more of a relief to the party. Now, that’s not so surprising. I have already commented on the rapid decline in membership numbers for LRM and LFI, as well as the participation rate in the LR presidential elections in December 2017. And it will also be interesting to see how many of the Socialists remaining 100,000 members actually vote in their leadership election this week. The bottom line is that parties always suffer in post-election periods. Still, the palmipède, as Le Canard enchaîné is also known, reported that in some departments the rate of subscription has dropped by 20-30%, while in Moselle, in the east of France, it is down 80%.

And so the Front National arrived in Lille, promising ‘un Front nouveau’ and selling coffee mugs with a compass pointing north-east, or possibly far-right, and bearing the words ‘I was there’…

Yes, but who in France uses a mug?

Now, while everyone loves a bit of merch, the party faithful might have been hoping for more than just another bit of crockery to put at the back of the cupboard, next to the Hénin-Beaumont Half-Marathon finishers mug. Most of the Saturday session had been set aside for unpacking the views of the membership of key questions, until Le Pen unveiled a surprise guest, none other than Time Magazine’s Scruff of the Year, Steve Bannon. (Okay, the scruff of the year bit isn't true.) His appearance was undoubtedly a coup and galvanised the congress while deflecting attention away from a lack of new ideas coming out of the refondation. (More of a dusting off of old ideas, reckoned Le Monde.)

Bannon was able to attend because he had come over to Europe to cover the Italian general election on 4 March and to make contact with the leaders of what he describes as an international network of national populist parties. Anyone else get the paradox of an ‘international network of national populist parties’? During the week, he addressed a meeting of the Swiss populist UDC in Zurich and also met the leaders of the German AfD.

Bannon’s appearance at Lille was organised through Le Pen’s partner, Louis Aliot and remained a secret up until the eve of the congress. It was also something of a coup for Marine Le Pen, because previously Bannon had focused on her niece, Marion Maréchal Le Pen as the rising star of the French far-right. The latter’s appearance at the CPAC meeting in Washington appeared to signal that she is preparing to come out of her temporary retirement from politics, sensing perhaps that her aunt is running out of steam.

Le Pen doesn’t quite look like she’s finished just yet. There were, of course, dissenting and disappointed voices at Lille: it’s not difficult for a journalist to find a congressiste to express their frustration that nothing seems to be changing. But Le Pen was cheered to the rafters whenever she spoke and Bannon went down a (worrying) storm as he told his audience to wear the accusations of being racists and xenophobes as a ‘badge of honour’ and was greeted by chants of 'On est chez nous'.

The main events on the Sunday were the election of the party president and executive committee and the adoption of new party statutes. Marine Le Pen was easily re-elected, with no challengers and just 2% of spoilt ballots. The election to the party executive was a little disappointing for her, with some of the old guard getting back on, but the key points are that Nicolas Bay and her new best friend, Sébastien Chenu were re-elected too. And, more importantly, her niece did not stand and so has no formal platform within the party, even if she might be planning a comeback before 2022. The next election of the party president is in three-years’ time and the party statutes specify that the head of the party is its candidate for head of state. Le Pen also had the satisfaction of seeing new party statues ratified, which included the abolition of the role of honorary president, i.e. her father.

La cerise sur le gateau, however, was the much-anticipated change of the party name, which had been mooted as early as May last year, after Le Pen’s defeat by Macron and as a means of reaching out to other parties to form an alliance ahead of the general election. Then, one of the suggestions was the Alliance Républicaine et Patriote, but Le Pen lost control of the term ‘patriote’ when Philippot set up his own group within the FN called Les Patriotes and then left to found his own party under that name. Various other options had done the rounds since then, but the lexical field of terms is limited, not just by ideology but also by others having already registered certain terms. Even the ownership of the name Front National was disputed back in the early 1970s and in itself it masked the quite disparate range of microparties that gathered together under the FN umbrella and Jean-Marie Le Pen’s leadership, from hardline Catholic intégristes to the defenders of Algérie Française to the nostalgiques de Vichy and white supremacist groups, or even the rump of French monarchism.

Nevertheless, Marine Le Pen had made it clear in the weeks leading up to the congress that, for her, if the FN is to become a party that can enter into strategic alliances with other parties and hope to govern, it has to change its name. She didn’t quite say that the name Front National has become a toxic brand, but that was her subtext.

Her choice, the Rassemblement National is not without its problems, perfectly well outlined in this article in The Guardian. In the first place, there are historical echoes of a collaborationist party of the 1940s, the Rassemblement National Populaire. In the second place, it’s been used before – by her father in 1986, not for a party but an electoral alliance that reached beyond the narrow confines of the FN. And in the third, according to a number of sources, the title has already been registered.

In itself, the term rassemblement is not problematic. It means assembly, group, union, coming together. Before it morphed into the Front Populaire, the broad left-wing anti-fascist alliance that won the 1936 French general election was known as the Rassemblement Populaire. In more recent times, rassemblement has generally been associated with parties of the Gaullist right. Thus, in 1947 Charles de Gaulle set up the Rassemblement du Peuple Français (RPF) and Jacques Chirac the Rassemblement pour la République (RPR) in 1976. Towards the end of the 1990s, Charles Pasqua, who was active in both the RPF as a young man and in the RPR as its main organiser, quit the RPR over its pro-European stance and set up a Rassemblement pour la France along with fellow Eurosceptic Philippe de Villiers’ Mouvement pour la France and took more seats in the 1999 European elections than the main RPR list, led by Pasqua’s former protégé, Nicolas Sarkozy.

Marine Le Pen herself had already used the word before, in the general and intermediate elections between 2012 and 2017, through her Rassemblement bleu Marine, aimed at establishing a bridgehead to right and far-right politicians and voters alienated by the FN brand.

Although the announcement of a new name was warmly applauded by the congress, it was in itself something of a disappointment. And of course, historians, journalists and politicians jumped on the announcement straightaway. On the Monday morning following the announcement, Igor Kurek, the president of what remains of Pasqua’s RPF, went on national radio to claim that he had patented the title and was in no mood to let Le Pen have it. As time went on, however, it turned out that Kurek had not actually registered the name and had left it to an associate Frédérick Bigrat (no, honestly, I didn’t make that up), whose name appears on the registration and who is, in fact, happy to turn the name over to Le Pen. Meanwhile the revival of the name Rassemblement National exercised a number of French historians, including the excellent, but by his own admission macroniste Jean Garrigues, given its echoes of Vichy and the execrable Marcel Déat. Rather than just a collaborator, Déat was a collaborationist who believed that France should not just put up with German occupation, but fully throw itself into becoming a full-on and unapologetic a fascist state.

Le Pen has left the adoption of the name open to a poll of the membership, to be decided over 'the coming weeks'. But the question is, will a new Rassemblement National appeal to or be able to reach out to other parties on the right? Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, leader of Debout la France, seems willing to open talks, as do the historic but tiny Centre National des Indépendants et Paysans. But the real target is an alliance with Laurent Wauquiez and Les Républicains (LR).

The tentation frontiste is one that has exercised the republican right in France for more than thirty years, but under leaders like Chirac and Philippe Séguin, and even Pasqua the line was clear. No collaboration with the FN. Sarkozy was less forthright, but preferred to combat the threat to his right flank by using the rhetoric of the far-right against it. His success at the 2007 presidential election was built, in part at least, on bringing a large part of the electorate that had voted for Jean-Marie Le Pen in 2002 back into the republican fold. By 2012, however, his failure to deliver on promises of immigration choisie and maîtrisée go a long way to explaining the success of Marine Le Pen. At the 2015 regional elections, Sarkozy refused to back Socialist lists better placed than LR ones in run-off elections against the FN, a position that drove a deep wedge between him and Christian Estrosi. And I have outlined in previous blog posts that while Fillon called for his voters to rally to Macron as soon as he knew he had been eliminated from the presidential race on 23 April 2017, Wauquiez’s position was that a vote against Le Pen was not a vote for Macron. Today, there are plenty of voices on the right of LR who think an electoral alliance with the FN/RN is acceptable or even desirable.

The latest of these is one Thierry Mariani, a junior minister under Sarkozy and Fillon. On the eve of the FN congrès de refondation, but in an interview not published until the Sunday in the Journal de dimanche, Mariani, who represented his native Vaucluse in the National Assembly from 1993 to 2010 before becoming transport minister, said that the FN/RN had changed, and that the time has come for the right to abandon its centrist allies and talk to the far-right.

You would be forgiven if you’ve never heard of Mariani. He’s not exactly a household name even in households where these things matter, but his provenance is revealing. Born in Orange, in the Vaucluse, in 1958, he was mayor of the nearby town of Valréas from 1988 to 1995. Elected deputy for department’s fourth constituency (Orange and its environs) in the right-wing landslide in 1993, he held his seat until 2010, when Sarkozy made him a minister (in France, as in the US, you cannot sit in government and parliament). He was also a regional councillor for Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (PACA) from 2004 until 2015.

The Vaucluse is one of the southern heartlands of traditional FN support, built on a strong pieds-noirs presence and throughout his career Mariani has faced the challenge represented by Jacques Bompard, a former member of the far-right wing movement Occident and a founder of the FN in 1972 with Le Pen père. Bompard gained national prominence when he was one of three FN mayors elected in the 1995 municipales, for Orange, a position he still occupies today. Bompard left the FN in 2005, out of frustration at Le Pen’s authoritarian style and, above all, his refusal to take local politics, the bedrock of the French system, seriously. After joining Villiers’ Mouvement pour la France, Bompard left after the MPF fell within the orbit of Sarkozy’s UMP. With regional elections looming in March 2010, Bompard set up his own Ligue du Sud, an alliance of small far-right groups, including the particularly charmless Bloc Identitaire, whose use of the wild boar as a symbol, linking them back to their ancestors the Gauls tells you all you need to know.

In those elections, Bompard lined up against an FN list headed by Jean-Marie Le Pen, a Socialist one led by Michelle Vauzelle, president of the regional assembly since 1998 and… Mariani, heading a majorité présidentielle list. Bompard was eliminated, with less than 3% of the vote and Le Pen, Vauzelle and Mariani went forward into the second round. But it was noticeable throughout the campaign that Mariani focussed entirely on the shortcomings of the ruling left-wing regional administration under Vauzelle and made very few attacks on Le Pen. Vauzelle won and his list’s 44% of the vote in the run-off gave them 72 seats to Mariani with 30 (from 33%) and 21 for the FN (23%). [French regional elections give the winning list half the seats. The remaining half is then allocated proportionally.] There was a sense of relief at UMP headquarters that the right would not have to face the embarrassing situation of an offer from the FN to form a coalition, not least because Mariani was difficult to handle.

In the summer of 2010, Mariani was one of a group of thirty or so deputies who rebelled against what they saw as government backsliding over immigration and security by setting up La Droite populaire, a group of right-wing frondeurs within the UMP. There also appears to have been an issue of a personal offence on the part of Mariani, who felt that he should have been appointed to a ministry already. In fact, the nomination came in the autumn, but the group remained and Mariani was a forthright supporter of the droitisation of Sarkozy’s second round campaign in 2012.

Mariani is, moreover, close to the Kremlin. He is married to a (younger) Russian wife, has visited the Russian occupied Crimea and also is a supporter of Syrian president Bashar-al-Assad. All of which makes him very lepéncompatible when it comes to geopolitics and media support. But there’s a further twist to this story. Regular readers of this blog might recall that I mentioned a new kid on the FN block, Sébastien Chenu, who came to the party from the UMP. According to Le Canard enchaîné (24 January 2018 again), Chenu has been pushing Mariani as a possible tête de liste for the FN/RN for the 2019 European elections…

Since the announcement of the plan to change the name from Front to Rassemblement National, the response from within Les Républicains, Mariani apart, has been muted. Wauquiez has been mired in a scandal of his own recently, after giving a series of lectures at a Lyon school of government where he imagined no-one would record the proceedings and where he slagged off various political figures whilst adopting a very clear identitaire posture. Wauquiez claimed that his provocative and populist approach was no worse than that of a young Jacques Chirac, evoking a time when the former president was known as ‘le bulldozer’. That claim in turn earned him a rebuke from former PM Jean-Pierre Raffarin that reminded me of Lloyd Bentsen’s comment to Dan Quayle during the 1988 vice-presidential debate, when Quayle compared himself to JFK: ‘Senator, you’re no Jack Kennedy’.

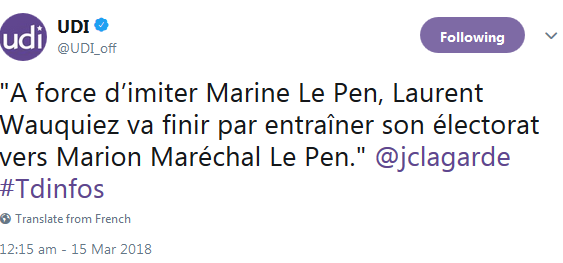

But Mariani has a point. In amongst the froth, he mentioned that he feels the time has come for the right to break once and for all with their former allies in the centre and centre-right. Let them get into bed with Macron and the éternel marais described by Maurice Duverger and revisited in a recent article in Modern and Contemporary France by Robert Elgie. For their part, some on the centre-right are thinking too that Wauquiez’s posturing is leading to a very clear separation that will not end well for Wauquiez, nor Marine Le Pen. The tweet below, from Jean-Christophe Lagarde, president of the Union des Démocrates et Indépendants is unequivocal. 'By imitating Marine Le Pen, Laurent Wauquiez will end up dragging his electorate towards Marion Maréchal Le Pen.'

Elsewhere, there is a feeling that Marine Le Pen has played her trump card (no pun intended) and that it has fallen flat, though that comes from Le Figaro, the LR’s daily newspaper, so it might be wishful thinking.