Emmanuel Macron and 'la présidence jupitérienne'

Speculation about who would take the official photo of Emmanuel Macron, and where, had been doing the rounds for some while. These things matter, because in due course, the portrait of the new French president will replace that of François Hollande hanging in every mairie in every commune in France and Navarre, all 35,000 of them.

At one point it was suggested the job might go to the photojournalist Mathias Depardon, recently liberated from a Turkish jail thanks to Macron’s personal intervention. But in the end, it fell to Soazig de La Moissonière, official photographer to François Bayrou in 2012, and to Macron for over a year leading up to the 2017 election.

You can judge for yourself the outcome, but once the photo was formally released, via Twitter and Facebook, the heavyweights started laying into it. The least you can say is that it represents a break from the past. Mitterrand the bibliophile and Sarkozy, who wanted to give himself an air of gravitas, had themselves photographed in the library at the Elysée. The two Corrézien presidents, Chirac and Hollande, preferred the gardens as the setting.

Macron is between the two. In his office, leaning against his desk, in what some have likened to a Francis Underwood (House of Cards) style, but the window opens onto the gardens. Framed by the tricolore and the EU flag, by his right hand are two mobile phones. There are three books on the table, including one by de Gaulle, but you’d have to know. The ink well in the form of the cockerel makes its point well enough, while the clock, apparently the one used for meetings of the Conseil des Ministres, seems to me to be an echo of Jacques-Louis David’s 1812 portrait of Napoleon I. President and photographer may or may not be aware of the reference, but David put the clock there to underline that Napoleon was working through the night (the clock says ten past four, the sputtering candle indicates it is night time) for the French people. And so it goes…

Source: Wikipedia, innit

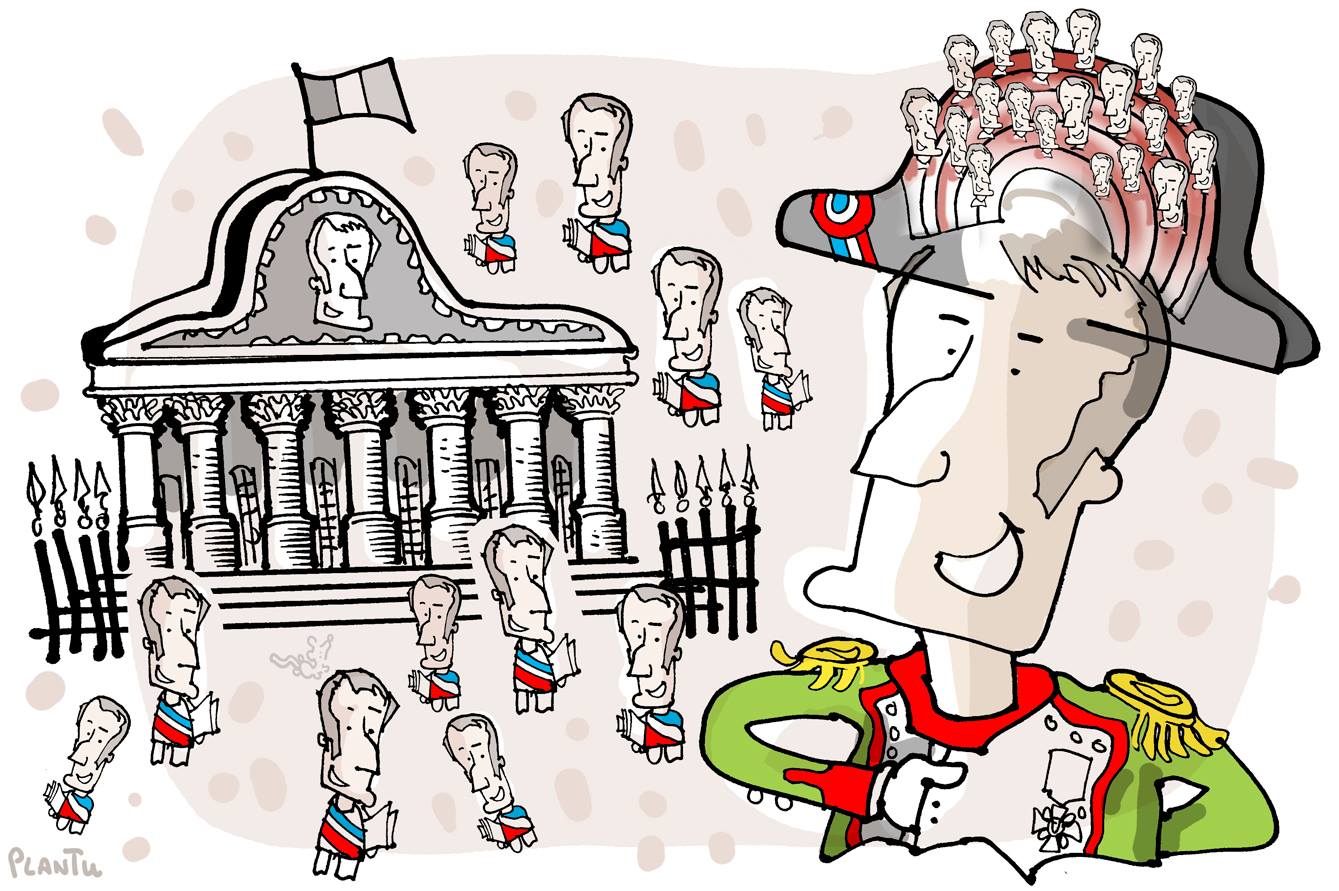

It won’t surprise readers to learn that the comparison of Macron to Napoleon has already been made many times over. Plantu, who draws Le Monde's political cartoon every day, produced this comment on the newly elected National Assembly on 26 June. Again, it very much speaks for itself.

Source: Le Monde, 26 juin 2017. (Plantu fans can get daily updates and access his archive by 'liking' his Facebook page)

The building is the Palais Bourbon, which houses the National Assembly. (It’s just across the Seine from the Place de la Concorde.) You’ll have spotted the roof in the shape of a bicorne, the two-pointed hat, with the bas-relief of Macron, as well as the mini-Macrons all decked out in their sashes, which indicate their status as élus, as well the semi-circular layout of the debating chamber (the hémicycle) on Macron's bicorne. Not great satire perhaps. Plantu so far seems to be pretty well-disposed to the new president, in a way he was not to, say, Nicolas Sarkozy. But I digress.

Last week (26-30 June) witnessed the first sittings (séances) of the National Assembly, which mostly focussed on the election of the new President (or Speaker) of the Assembly, the executive bureau and the key posts in the commissions, which we would translate as standing committees, although they have more impact on the legislative process than in the British system.

I have hesitated, in my work on the French Senate, to use the word Speaker for the President(s) of France's assemblies, because to the British mind it suggests a politically insignificant figure. Presidents of the two French chambers play a key role in the political architecture and are often influential in party politics too. One thinks, for example, of the role played by Gérard Larcher, the Les Républicains President of the Senate, during the circus that was the Fillon campaign. The President looks rather more like a leader of the house/majority, where there are several groups involved. What is more, the President of the National Assembly is, according to protocol, the fourth most important figure in the state, after the President, the Speaker of the Senate, and the PM. (In the absence of a vice-president, in France, if the President dies or is removed from office, the Speaker of the Senate becomes the interim head of state until the election of the new President.) But, stylistically, it is useful to use the term Speaker to distinguish the post from Head of State. In any case, in the US context, the Speakers are not insignificant figures.

So, on Tuesday 27 June, deputies elected their Speaker. No very obvious candidates had emerged during the general election, but in the end it was François de Rugy, a former ecologist who had run in the left-wing primaries and then defected to Macron, who was elected by the LRM/MoDem majority.

The bureau of the assembly, the executive committee that oversees day-to-day management, comprises 21 other deputies, in addition to the Speaker. There are six vice-presidents, and by recent tradition four of these go to the majority, two to the opposition. The twelve posts as secretary are divided in the same ratio. Nominations are handled by the groups and put forward by the chairs of each.

All went reasonably smoothly with this part of the process, but there was an almighty row over the allocation of the three posts as questeurs, the officers who oversee the financial running of the Palais Bourbon. Les Républicains (LR), in their position as the main opposition group, had expected to see their candidate take the post. Instead, LRM deputies backed Thierry Solère, a former LR member behind the creation of the centre-right bridge group made up of pro-government LR deputies and the Union des Démocrates et Indépendants (UDI). Cue indignant harrumphing among the right-wing opposition and from the far left La France Insoumise group, the Gauche Démocrate et Républicaine (the Communists and their allies), as well as the Socialist rump, reborn as the Nouvelle Gauche. And out on the streets of France... nobody cared.

There then followed the appointment of the chairs of the eight commissions. Again, by a not-actually-very-old tradition, the chair of the most important, finance, goes to the opposition. And this time it did, to a former Sarkozy minister Eric Woerth. The others all went to the majority. As well as presiding over the standing committees, the chairs sit on the conférence des présidents, along with the Speaker, the vice-presidents and the chairs of the parliamentary groups, to decide the timetable, who will be permitted to speak on what and when and which private bills will be heard. The allocation of time to speak is determined by a formula driven by size of group, although more time can be allotted to the opposition if the conference agrees.

In due course, deputies register their interest for one of the commissions and are allocated according to group size and by lots and for many of them, their real contribution to parliament will be as committee members, proing over legislation, hearing propsals for amendment and so forth. Here, rather than in the debating chamber, is where reputations are made.

The next phase of getting parliament up and running came today, Monday 3 July, in a new departure, when Macron addressed both houses, meeting at Versailles and sitting in a joint session, known as le Congrès.

A lot of unnecessary fuss has been made about this.

The actual business of both houses sitting together is not new in itself. Under the Third and Fourth Republics, the head of state was elected not by the people but by parliament, and they met in this way to elect the President. Under the Third Republic, le Congrès was also the only place that constitutional reform could take place. Under the Fifth, it serves as one of the places constitutional reform can be ratified, under article 89 of the constitution.. And since 2008, following a raft of constitutional changes passed under Nicolas Sarkozy (by le Congrès), it has been permitted for the head of state to address parliament directly, once a year, at a meeting of le Congrès at Versailles. It has only been used twice. Once by Sarkozy in 2009 and once by Hollande, in 2015, in the wake of the terror attacks in November of that year.

Why Versailles? It has nothing to do with the Sun-King and everything to do with Versailles as the birthplace of the French Revolution and the modern French parliament in 1789. It has everything to do with Versailles as the seat of parliament at the refounding of the modern Republic in the 1870s. It has everything to do with Versailles being the place that votes of le Congrès have always taken place, either to elect a new President or to revise the constitution. And it has everything to do with the fact that neither the National Assembly nor the Senate can fit into one another’s debating chamber, or hemicycle. So there.

Where Macron is innovating – and this is what is putting noses out of joint - is that he clearly intended to use the speech as a ‘state of the union’ address, at the beginning of his term and that of parliament, to outline the broad roadmap for his quinquennat (the five-year term). This has not been done before, at least not directly, and the fact that it took place the day before his PM Edouard Philippe is due to outline his government’s legislative programme caused some (frankly a bit thick) commentators to describe Macron’s decision as an insult to his prime minister. It’s nothing of the sort. It is also worth noting that Macron has indicated that he intends this to be an annual event.

Macron spoke for more than an hour, his first major public intervention (which might explain why the media have been so vexed by this), but as he himself argued, it doesn’t seem unreasonable for the President, elected by the people, to outline his intentions to the representatives of the people, their deputies and senators, in a speech that is televised live. Still, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, whose radical agenda has extended to refusing to wear a tie in the National Assembly, described it as the act of a ‘monarch’ and announced that neither he nor his La France Insoumise colleagues would attend. Quel dommage. A handful of other deputies made the same decision.

There is an account of the speech here for English readers (though the seat of kings thing has me spitting feathers – the royal palace was in fact the Tuileries) and French readers can find it in the French press – Le Figaro has a good synopsis here. Amongst other things, Macron has promised to end the state of emergency this autumn and to take on some pretty significant institutional reforms, including PR and a reduction in the number of deputies and senators.

For the last of those reforms to be carried out will require a revision of the constitution and if it is to go via the parliamentary route, it will have to pass both houses in identical form (Article 89). Macron does not have a majority in the Senate, so it could get sticky there and Macron is threatening that if parliament refuses, he will use a referendum. Given that all the candidates for the presidency argued for a reduction in the size of parliament, however, it seems unlikely that the upper house will rebel...

One other reason that this is the first time Macron has made a major intervention in public is that his reserve is part of his determination to be what he has described as ‘le président jupitérien’. That sounds pretentious in English and, I’ll be honest, it does in French too, but Macron's options were limited. He would like to be a president in a style somewhere between de Gaulle and Mitterrand, but to claim one or the other would have been antagonistic. What Macron was trying to convey is the notion that he will be a President who, unlike Hollande, actually governs and who wants to govern. Hollande promised to be 'le président normal', but in the end was simply inadequate. But Macron also does not want to be seen in the same light as Sarkozy, the hyperprésident involved in everything.

That is not to say that Jupiter, king of the gods, is not all-powerful, but that his descent from Olympus will be less frequent and less obvious. The government will be allowed to govern, but it will do so under his under his very firm guidance. This is what the French expect of their president. Above all, Macron is determined to remain master of his own time and not be forced along by a media agenda, in the ways that Sarkozy and Hollande were.

Macron will try to make the weather, but to suit him and use thunderbolts less frequently. When Sarkozy was President, Gérard Larcher was very critical of 'Sunday night fever'. Sarkozy would be briefed on Sunday evening of what had happened over the weekend, would then contact the government to order a legislative response on the Monday to be put to parliament on Tuesday. Macron says there will be less law-making. On verra.

So, tomorrow (4 July), Edouard Philippe will go to the Palais Bourbon, armed with his immediate programme for government for the extraordinary session that will last until the end of July. He will then submit his government to a vote of confidence, under Article 49, he will win the vote and parliament will finally crank into action.